by The Marginalized Mazola Queen © 2006

Damn the sadists, damn even more the indifferent normal Americans who know what they were doing, in doing nothing. – Randall Robinson, Quitting America

It is rare to stumble upon a written work that resonates so profoundly with your own experience in and perception of the world as to stay with you for days, months, years, lifetimes even—echoing in the chambers of the heart, the soul; rattling the rafters of the mind, fueling Sisyphean efforts to move men and mountains or quixotic quests eliciting answers to unposed questions. There is solace in knowing these thoughts have been thunk, these bitter truths drunk, these poisons poured before. This salt. These wounds. These bitter ironies.

Authors whose works resonate with me that way have typically been those whom many of my “fellow Americans” find uncomfortable—authors reviled as “unpatriotic,” rejected as “militants” and relegated to the trash heap of history’s mishaps and misfortunes in the American “mind.” Malcolm X, Mary Daly, Ward Churchill, to name but a few.

These authors are more often than not dismissed as “haters” by readers for whom their words apparently do not resonate, for whom they may even offend—or otherwise rile and discomfit. But what I have always found inspiring about these authors’ works is the undying love of their people so clearly vested in their every other word, and I’ve always wondered about the way responding with outrage to indignities suffered by loved ones somehow translates into “hatred” by those who are not necessarily “hated,” but simply are not objects of love for these authors. The absence of love is not hate—except to a self-adoring audience of onlookers that has grown so accustomed to being showered in loving affirmation that its mere absence apparently feels something like hate to them.

I am reminded of Elie Wiesel’s adage: the opposite of love is not hate, it is indifference. Accordingly, I would propose that the antidote to indifference is love. And I see this as the common thread speaking to me from these authors’ works. Love. For their people. For the planet. Love. Of meaningful life. Love. As antidote to the collective indifference American society has bestowed upon certain groups of people in response to legitimate “complaints” whose validity has either been patently dismissed or formally acknowledged in spirit, but subsequently ignored in deed. Love as antidote, perhaps even as cure. The correction of an imbalance.

And the bitterness? Perhaps there is more than a taste of it in their works. A bitterness perhaps born of bitter—indeed, mordant—irony, the irony of reversal. And projection. When you love the “wrong” people and respond with bitter indignation to injustices they have suffered and injuries they’ve sustained, you are likely to be scolded schoolmarmishly for your “bitterness.”

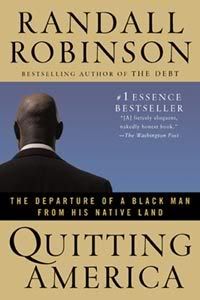

An author recently crossed my path whose words are now permanently cataloged in my life’s library like well-worn reference tomes in the reading room of my mind—words like cold comfort packs to still the slings and arrows. The author is Randall Robinson, whose most recent work, Quitting America, is a personal narrative explaining why it was impossible for him—a native-born American Black man—to continue living in this country. Predictably, the book has been described as “bitter” by some no-name reviewer with less than a fraction of the man’s prodigious credentials.

While Robinson's sarcastic skills are extraordinary, his bitter tone will make some readers close the book before pondering his evidence.Oh. The bitter irony, the acrid arrogance of it all. Lo, the “bitter” Black man seeking to squeeze something soothing from the astringent white America applies to the injuries and insults he’s sustained on the killing fields of contested history. Bitter irony. Bitter truth. Bitter, bitter, bitter.

I found in Robinson’s Quitting America ample substantiation for many of the things which prompted me to leave this country in 1984 on a near decade-long stint as an X-pat in Europe, and perhaps that is one reason Randall’s words struck me as they did.

So for example, it would be tempting to attach some statement along the following lines, to every word of “social reporting” I write:

All social reporting is subjective. The difference here is that I readily confess this. My opinion, my measure taken, is but a small bit of what could resolve with other bits into a collective and useful truth about anything. Or perhaps all of this business of truth-seeking is just so much bullshit, just so much palaver to disguise the ugly, ongoing, atavistic tension between egos and classes and genders and ethnic groups and races. Thus I can only do my best to describe things to you as I, this race-victim shaped American, see them in a country markedly different from the America I have left, in every likelihood, for good. Of course, like everyone else, I can only see through the prism of my own experience, through the pain of what happened to me, what happened to me in America at the hands of white Americans.What is more, Randall’s reasons for quitting America shortly before “9/11 changed everything” were eerily like my reasons for leaving over two decades ago. He writes:

[T]he war had nothing to do with my reasons for leaving. The reasons are not easy to organize and write about, scattered as they are in sobering, disillusioning bits and pieces across the changing fields of a lifetime.And furthermore, pointing to a tendency that has burgeoned exponentially in this country in the twenty years since my own absolutely mortified-in-my head leavetaking in 1984—one that the Bush regime has magnified beyond the point of caricature, Robinson writes:

All societies have ugly sides to them, I suppose, and it stands to reason that ours, the most powerful of societies, would disport on the hide of its overall behavior a few large and unattractive warts, the most repellent of which being the seemingly unconscious habit of denying that American society is, like all other societies, flawed in the least.

This refusal to examine, to look at itself at all, as would virtually the rest of the world, has produced, or perhaps is produced of, a collective national psychosis, accommodated and protected by layer upon layer of an orchestrated self-adoration that only great power could insulate from effective critical assault.

Americans don’t know how to be equals. No, I am not referring to the less important vagaries of material difference, economic or military, but rather to human equality, that essential quality of self, foreordained as God and nature’s democratic idea for all who make up the human family. The American mind cannot absorb, cannot wrap itself around notions like this; hence Americans including black soldiers who are little more than agents of the American empire, feel just fine about doing anything to anybody. They do not believe that they are being attacked in Iraq because they no more belong there occupying someone else’s country than Iraqis in tanks and full battle gear belong on Pennsylvania Avenue. But you hear Americans talk—Republicans, Democrats, rich people, poor people—and you come to understand that Americans, many of them otherwise the nicest of people, literally believe—no, know--that they cannot, by the psychotic power vested in them by the state of themselves, do anything wrong.I’d never heard of Randall Robinson before this book jumped out at me from a shelf at the local bookstore a few months back, but I subsequently looked him up on the Net. George Kelly’s Negrophile.com blog describes Robinson’s as the Kind of Voice that Startles Conventional Wisdom with its Unfamiliar Perspective and says:

It's not that Randall Robinson hates America. It's just that this country has consistently disappointed him and all people of color, he claims in his new book, "Quitting America." And in case someone responds, "If you don't like it, why don't you leave?" -- he did.Robinson is founder and president of The Transafrica Forum; additional background on the man’s career and accomplishments can be found herehere and here. Democracy Now! conducted an interview with Robinson in March of 2001, when Jean Bertrand Aristide (with whom he is good friends) called him (!) to report on the American-backed overthrow of the Haitian President, and again in March of 2004 , when Mr. Robinson was part of the delegation that accompanied Mr. Aristide on his return to the Carribbean. The October 2005 issue of The Progressive features an interview in which the author elaborates on his reasons for leaving the country of his birth. In addition to several book-length works (The Debt; The Reckoning; and Defending the Spirit), Robinson has published articles in The Nation, Counterpunch and elsewhere.

[...]

Three weeks before the Sept. 11 attacks, Robinson officially "quit" the US and moved to St. Kitts-Nevis, the small Caribbean island nation where his wife had been born. "Quitting America" details the circumstances that prompted him to leave, in prose that is alternately lyrical, logical, and furious.

Now that I have finished reading just one of Randall Robinson’s works, I am nearly convinced that there is something very Shabazzian about this American X-pat. And so it is likely that he will be cataloged along with the rest of the greater and lesser “haters” of the world—“haters” like my friend Mary Daly, “haters” like my friend Ward Churchill, “haters” like me who take love to be the antidote to indifference, but who apparently love the wrong people or are defined as “haters” based on the absence of great love for certain other groups and classes of people—first and foremost amongst them, privileged white males.

No doubt, most left-leaning liberals in this country will agree that Mr. Robinson acted with utmost integrity when, in May 2003, as he was to be awarded the honorary Doctor of Laws—Honoris Causa--by the prestigious Georgetown University, he declined the degree after discovering in a Washington Post article that the university had invited former CIA director George Tenet to speak at commencement ceremonies there—to the enthusiast response of graduates.

Mr. Robinson’s statement, which he was never afforded the opportunity to deliver, is sure to find resonance in liberal progressive communities:

I wish to begin by apologizing to all of you if what I am about to say on your day causes you discomfort.On the merit of that act alone, one would think the man commands the attention of any self-respecting liberal or progressive in this country—but, if responses to his work on some of the countries most highly-trafficked liberal blogs are any index—Robinson’s thoughts on race and race relationships in this country are more likely to earn him a sound measure of billingsgate than the praise he so richly deserves.

I have fought all of my life against social injustice. I live on the tiny democratic Caribbean island of St. Kitts. I only learned this morning that George Tenet, the director of the Central Intelligence Agency, was to be the speaker at your School of Foreign Services exercises yesterday.

I sincerely believe that in the years ahead, the entire world will come to accept that the United States has committed in Iraq a great crime against humanity, a crime against innocent Iraqi women, children and men, indeed, a crime against our own men and women, who have paid and will continue to pay with their lives for the greed of America’s empire-makers.

In my view, President Bush, Secretary of Defense Rumsfeld, Secretary of State Powell and Mr. Tenet are little more than [deleted]. There are no weapons of mass destruction in Iraq, and they knew this. There is no Iraqi connection to 9/11. There was no legal justification for a war in which we have not even bothered to count the Iraqi dead.

America has committed an awful wrong. In the sight of God, I trust in time that this will be the prevailing verdict of humanity.

In any case, you have chosen the wrong person this morning. I should not have come. Indeed, I would not have come had I known before what I learned this morning when I opened the newspaper.

Americans must choose. They must choose between decency of course and empire, between morality and [deleted], between truth and deception.

Mr. Tenet has the right to speech protected by our Constitution. But that right should not be exercised on a platform so broadly respected as yours.

I cannot accept your honor. For in my view, Georgetown University disqualified itself of the moral authority to bestow one.

My candle lights little other than the interior of my own conscience. But for me, for all my life, that has been enough.

The remainder of this piece consists primarily of extensive quotes from Robinson’s most recent work—it is a record of the words now highlighted in neon pink in my copy of the book. I have taken the liberty of departing from the order they appear in the book, arranging them according to what I think is most likely to resonate with liberal-progressive readers, especially in online communities. I have not provided page references—readers are better advised to purchase the book and reflect on it according to their own inclinations!)

I’d like to place this one in fine print on every page of my US passport while traveling abroad this summer:

It just galls me to have my fate determined by a man as patently mediocre as the president.And what self-respecting liberal progressive could fail to applaud Mr. Robinson for these gems:

Among all the world’s leaders only President George W. Bush could accomplish the outcome likely to be in the offing, notwithstanding what happens on the battlefield. In one cruel and foolish gambit, the president has, in Egyptian president Hosni Mubarek’s view, created “a hundred Osama bin Ladens,” weakened moderate and “friendly” Arab governments, galvanized an infuriated Islamic world against the United States, and launched into legend, where time forgives all sins, Saddam Hussein, who will be remembered in lore only for his brave stand against the snorting American bull in Iraq’s small nook of the global china shop. A dubious David against techno-Goliath, practicing asymmetric warfare—guerrilla tactics, fake surrenders, soldiers in mufti, suicide bombers—to offset the bullying techno-behemoth’s advantages for just long enough to win the admiration even of those who have every good reason to detest him.

What, indeed, is the source of my leaving the country of my birth? Could it be that I, too, believed in science, only to learn that science had failed me? That I had been duped—duped into believing that all of humankind shared, if little else, a common species? If I any longer believed such to be the case, I would choose, if I could so choose, to resign from that species, to reject its broad brackets as intolerably repugnant, rather than share even that small invented rubric of classification, that academic common ground of species, with the likes of George W. Bush, Donald Rumsfeld, Condoleeza Rice, Colin Powell, and all the unsettlingly toneless generals who’ve allowed their humanity to be trained out of them. For what species member, recognizable as such to me as mine, could put a hand to an implement that could—indeed, would, knowingly would—snuff life cruelly, brutally, violently, randomly from anonymous innocents. And afterward, on the afternoon of the morning of the red nights, go home for supper, to kiss the wife, play with the children, listen to Bach, walk playful, leaping dogs on a green, green lawn.So far so good.

I used to believe it was just the Germans whose souls were cauterized, but now I am not nearly so sure of that. After all, a large majority of the German people believed that they were right when their armies rolled into Czechoslovakia and Poland. As hard as it may be to believe, the American people may possibly have made themselves believe that the regime of Sadam Hussein (who can’t put a plane in the air) represents a real and immediate threat to American freedoms, but I don’t for a minute believe this. It could well be, however, that one gets the unexamined result of a “Goebbels Cocktail” when one mixes the self-administered mantra lie into the deep vat of American arrogance, and then peppers the powerful stew with ample amounts of racial prejudice.Robinson's statements on the role of the press are spot on:

American generals and their soldiers, I am convinced, actually believe they are right, even as they invade someone else’s country, rumbling over the terrain in caravans of lethal armor, spread-eagling, handcuffing, body-searching antiquity’s locals, flying their murderous sorties, sometimes two thousand a day, bombing all night, every night, bombing not just strategic targets, but a children’s hospital and markets and, for some improbable reason, the Iraqi Olympic Games headquarters building.

Still, they blame the victims. It is this peculiar material form of popular American insanity that frightens me. They just don’t get it, these chillingly one dimensional, opaque Americans. They don’t get any of what the rest of the world gets easily enough, except their English and Australian blood-mates. You beseech them.

Please read this twice and slowly. There is no acceptable justification for killing civilians or soldiers or anybody else when you are invading their country. It is their country and your reasons for assaulting it are globally assessed as specious. A regime change your president promises with his silly little boy smile. Unilaterally. Eight thousand miles from his doorstep. What nerve. What gall. Small wonder you are distrusted so. Go home, for God’s sake. Let some heaven-sent wind of unfamiliar humility fill your tacking sails and blow you there before you wreck the community of nations and its undervalued house of assembly, the United Nations.

An unfortunate characteristic common to all governments (democracies, dictatorships, hybrids) is that those who speak for them are almost always obligatory liars. Little of what they say to those they govern can be taken at face value. This trait is inherently less detrimental to public well-being in a democracy than in a dictatorship, owing to certain basic rights pursuant to which individuals and groups in a democracy can question the truthfulness of what their government tells them. That is, if such individuals and groups have available to them alternate, independently obtained information upon which to construct a credible public challenge. This inherent advantage that democracies enjoy over dictatorships is now being eroded by low-road journalism practiced by the new ratings bottom-fishers, FOX and CNN.

I suppose none of us will be teaching Robinson in the near future, for fear of losing our jobs for mentioning the fact that some people have drawn parallels between contemporary America and Nazi Germany:

More powerful than Nazi Germany could ever have dreamt of becoming, the United States is now the unrivaled ruler of the world and militarily overwhelming enough to unveil before a stunned family of nations a new concept of global hegemonic leadership, to wit: preventative war, pursuant to which, America alone at the pinnacle of power awards itself the “right” to attack any country that America deems a “potential threat.”Amazing stuff. Clearly, this author has a gift for speaking tough truths to power. And I think most liberal-progressive bloggers would all agree that he is a master of his craft.

However, at this stage in the game, you don’t have to look very far to find equally formidable minds speaking these truths to power: Frank Rich, Stephen Colbert, Lewis Lapham, and many others very own could ably compete with Robinson on the speaking “truth to power” scale.

But these are not the passages most likely to rankle liberal-progressive thinkers, nor are they the ones that speak most profoundly to my concerns as a writer and radically-minded intellectual. These words are not rare enough to pass the “make note of this quote”-test, not for my tastes. I don’t consider them any more exceptional than much of what I read on a day-to-day basis. I have included them here as the proverbial “carrot” to lead potentially resistant readers to the meat of the matter. A spoonful of sugar, as it were, to help the medicine go down. Because in my view, it is Robinson’s candor and courage in explaining—honestly—his “social” and perhaps “spiritual” reasons for leaving this country that get to the heart of the matter. And those truths—the ones that shoulda/coulda/mighta been “spoken to power” before “9/11 changed everything” are the ones that now must be spoken to power. Now that Katrina changed absolutely nothing.

I admire and appreciate Robinson’s percipacity, the acuity of his insights, his willingness to take risks and to speak the whole truth to power, not just a glinting little sliver of truth to leave a small incision in the shallow surface of our collective identity as Americans, but truths that cut to the deep subcutaneous quick. Not least of all, I am stunned by his mastery of the writer’s craft—so much so that I feel compelled to present the passages that moved me perhaps most because they reflect and affirm my experience and perception of America—not only by virtue of the deep insights they provide, but also on their merit as exemplars of finely crafted prose.

Many a liberal-progressive reader is likely to “take offense”at many of Robinson’s statements. That alone is disturbing to me. How can one take offense at a human being’s honest, forthright expository narrative about his own life? Robinson is not presenting an argument, he is not throwing out points for debate. He says (I repeat the quote) “I can only do my best to describe things to you as I, this race-victim shaped America, see them in a country markedly different from the America I have left.” I don’t think he’s asking anyone to “agree” or “disagree”—and you can’t really disagree with what is essentially a “memoir” anyway—unless the author is Robert Frey and you are Oprah Winfrey!

But there will inevitably be those who feel the need to question the “validity” of his “claims”—to balk, to stutter, stammer and stomp. To hem and to haw. But there are no “claims” here. He is simply “telling it like it is”—for him, in all likelihood for millions of other Americans, certainly for me (and I’m not even Black!).

There is nothing to “argue” about here. This is one man’s experience of America—and here sits at least one fellow American who can “relate” very well to this experience. Robinson’s is the report of a Black man who “made it” in white society. This is no “tale from the Hood.” As Robinson explains, “No, money ain’t the real problem. Not by a long shot.”

I suggest that anyone who doesn’t like the fact that these words reflect the experience of some Americans, rather than take offense, get up, walk out the door today or tomorrow (better yet every day for the rest of your lives) and ask: what can I do today to demonstrate with my actions that I am not indifferent to Black people? What can I do to express—in word and in deed—my love of Black people? How do I express my lack of indifference? Because if the opposite of love is indifference, then love is also the opposite of indifference. Hate need not so much as enter the picture here. No one is accusing white America of “hating” anyone, no overt racial animosity, the charge is by and large: indifference. Collective indifference. As Robinson put it, “not giving a shit,” as I have stated (repeatedly) in my own writings and conversations in liberal-progressive communities, “not giving a flying fuck”--and if there is one thing distinguishing my perception of America from Robinson’s, it is that, in 1984 I realized white people really didn’t give a shit. And I left. Today, it’s worse: they don’t give a flying fuck. And there are no polite words to describe that level of indifference.

Katrina changed everything precisely because it changed nothing. The cover has been blown on the pretense of caring.

Here, in no particular order, moments in the narrative that moved me.

(Many of these quotes were culled from the book’s first chapter, as excerpted in full here).

Americans are suspicious of selfless generosity.

Americans wrap themselves so tightly in the coarse cloth of their own everything that they can see little else beyond the shores of their own unmarked, unseen cultural insularity. This condition stewed in a pot laced with a pepper of deeply socialized racial assumptions can cause Americans to behave quite awfully.

America is a big place. Everything about it is big. It has big buildings, big streets, big guns, big money, big power, big hubris, big wounds. Everything about America is big except its people, who, unbeknownst to most Americans, are mere human beings, no bigger or smaller than human beings any place else in the world. They only look smaller, or behave smaller, because they come from a country where everything else, besides them, is so lethally big, so crudely antagonistic to the naked human’s social requirement.

Why then have America and Americans behaved so callously toward governments and peoples who present them with no threat but only proffers of friendship? Perhaps Americans, or more specifically, white Americans, have behaved such because they only really value or respect what they either crave or fear: money or might, all else to be belittled, disdained, dismissed, even desecrated. Could it be that in America, the unexcelled bigness of all things material has resulted in the concomitant relative smallness of all values nonmaterial? Moribund ethics. The death of the spirit. An unexamined and withering national soul. The commercialization of everything from school to pew.

Most white Americans in their dealings with black, brown, and all other varieties of nonwhite people are altogether well-mannered and are often all the more damaging for it. For indeed fine manners and America’s national opiate of choice, chauvinistic narcissism, combine to immunize white Americans en masse from self-knowledge, self-doubt, self-criticism. If they don’t like us, it is only because they are jealous of us.

As a practical matter maybe it wouldn’t be such a big deal, were not such coarse little bricks being hurled willy-nilly across the world daily by brainless, insensate white Americans, high and low, numbering in the thousands. And no, I have not suffered an inexplicable lapse of language judgment. I use the words brainless and insensate advisedly, if perhaps somewhat desperately. White people around the world insult black people, brown people, everyone-but-them people, regularly and gratuitously, without even the bitter, dubious flattery of conscious intent.

I am just guessing here, but I think when Americans say that America is the greatest country in the world, they mean only that it is the richest and most powerful, that their country meets all the bigness tests, that Americans have more stuff than anybody else, and that they can just flat shoot everybody else’s lights out. This is what they must mean. I don’t think they can mean that Americans are the happiest people in the world, or the most well-adjusted people in the world, or the most moral, or anything like that.

The truth put squarely is that I am spent, having fought too many American social battles that should never, in a more decent society, have presented themselves as such to begin with. I am no longer a normal person, as it were, preoccupied, as I have been constrained to be, with race and all the wearying baggage that rakes heavily in its train. But, of course, America had scarcely noticed me, not least that I was weary, preoccupied as America was with the taxing obsession of its unrelenting self-adoration. All along, I hadn’t really needed all that much. Once it may have been enough to know only who was responsible. An official confession of all the lurid details, a report, for once, of brutally candid self-investigation, a book from on high of awful truths about what all had been done to me and why. A compendious volume replete with the beneficiary’s moldy detailed records, journals, charts, graphs, ship manifests, U.S. Treasury receipts, contracts, balance sheets, pictures, plans, pen-and-ink drawings, memoirs of my 346-year-long legal destruction. The long overdue mea culpa that a nation like Brazil, riven with the freight of its own ugly racial past, is brave enough to issue, but America is not. Write the thing, damn it! Explain my stolen story and give it back to me, to the world and, indeed, to that quarter in as much need of it as I, yourself. Ask yourself: Would you have done any better, had you been in my place and I in yours?Early on in the narrative, Robinson introduces readers to “Man-Boy”—the name he assigns to a figure that will be familiar to any “indigenous” member of a poor, predominately red, black, yellow, or brown community in America, and especially so to those of us who have since moved on to “greener pastures” as it were. He describes his encounter with a group of adolescent black men, “floppy caps turned backward over black rags, pants bagging low over haute hood sneakers.” He calls them, “slavery’s harvest”—“children of long-sown seed, old burned Civil War cannister packed with live grapeshot, marked: DANGEROUS IF NOT TREATED.” He describes himself as “an escapee, a lucky victim with lucky loving victim parents.” And all of us who have similarly survived understand what it means to “navigate the slouched ranks of our future,” this encounter—from a position of privilege and prosperity--with the “utter hopelessness” that has descended upon the places of our birth. In America.

I no longer grind my heart against the cold rock of a sightless soul. I know now that this America, that I am, at last, reclaimed to have left, uncoupled, at last of its glittering spiritual anchorage, could never confess any wrongdoing, small or large, old or new, the powerful feeling, now more than ever, no need to learn, in the nation’s middle age, the painful craft of moral honesty.

But still you must understand that I, like any other human being, needed to know things about who I was. A need felt in an earnest child’s breast all the more pressing because you had metronomically instructed my parents, and theirs, and theirs, that they and I had originated in a dark forest of savages. I hadn’t believed this. Quite. Maybe. Not all of it anyway, my tender child’s spirit fighting for its life much too early, before my bones had finished forming, before I scarcely knew what race was, before, long before, I learned that some would never even notice my humanity. Who could have done such a thing? What had I done to anyone on high by the small age of five?

And Robinson, the high-powered attorney and international human rights activist, living the good life—in the truest sense of the word—with wife and child in the Caribbean?

He writes:

[H]ow am I different from Man-boy, save that I am the same machine with rationed opportunity’s optional equipment: Man-boy-eloquent, Man-boy-educated, Man-boy funded? But off the very same white, Western-world assembly line that has produced Man-boy for 346 years.

Difficult but simple enough were the problems that obstruct my course soluble by money alone.

No, money ain’t the real problem. Not by a long shot. But even should I try, I cannot explain to this Man-boy looking at me, for we are not joined to each other by any common memory, old or new. Nor can I find a common language with which to speak to his spirit, because some committee of the nation ordained long ago for such talks has killed it. Has killed his spirit and buried it under the rubble of the nation’s more pressing business.

Man-boy once had a family but it was dismembered by slavery like a life-giving river dammed generations before, many lifetimes upstream. He had a house that wasn’t much to speak of, but his homelessness is spiritual in any case. He had a father but his father was run off without his manhood centuries ago. And he had a mother (which was about all he had left) for whom mothering under the weight of America could be likened to the futility of a salmon struggling spastically to swim up a parched arroyo to spawn.

He had a history, a story of his people, that began on a plain in Ethiopia when humans pulled themselves upright thousands upon thousands of year before. But he had not been told his story, thus he believed, unlike the people of other races, that he had no story to be told, no tapestry of ageless accomplishment. He had been, millennia before the birth of Christ, produced of an oral tradition that had carried like an eternal stream all of the vitals of his spiritual identity forward—the names of his ancestors treed out well in the mists of Africa’s glorious antiquity, the rituals of a timeless familyhood, the ancient practices of religious ceremony, the embrace of a time-honored culture that shielded his soul from outside assault as the skill would protect the human brain. But that was long ago. And he doesn’t know a damn thing about anything except that he is cold in Rochester and feels the near-tactile grip of the biting wind.

I know of no other example in the modern world where millions of people from a single racial group had been stripped of everything save respiratory function—mother, father, child, property, language, culture, religion, freedom, dignity, and sometimes, even genitalia.

So now, I have left, and begun to know, all too late, what social normalcy can feel like. In the sight of God, now, make your statement. Dedicate it to Man-boy. Tell him who he was. Tell him who he is. Tell him why who he is is not who he was. Tell him the five-thousand-year story of his people. Tell him where and how you entered his story. Why you lied to him. Why you blighted him his one bequested memory, invented another, implanted it and scrapped him, standing dull-eyed on a frigid Rochester [NY] corner in mid-afternoon. Tell him. And tell me, too, while you’re at it.

Seen against all other societies that, like living organisms, surge and ebb, the deterioration of American society has been alarmingly rapid, although it may not seem so when measured with the short ruler of one subjective, adaptive life. People generally have little ability to compare a current social condition to a previous condition from which they have gradually been extruded, or not known at all. They have even less ability to compare a current social condition to conditions of life in distant cultures about which they know little or nothing of anything accurate.

[...W]hat is the value of democracy if our opinions are formed, our appetites manipulated, our values shaped, our decisions made, our most fundamental human needs camouflaged by the puppet-masters of politics and profit? Could it be that the cultivated obsession of firstness that makes America a rich and powerful country also makes it a sick society under homicidal siege to the enlarging ranks of its alienated and forgotten? Could it be that lost in the deafening noise of excessive pride, wisdom of public course has become all but impossible to come by?

Truth is elusive, even when vigorously searched for, and America can clearly make no pretense to such. For it has tricked itself and preserved its self-adoration by mistaking wealth for worth.

Don’t you think Americans need to sit back and attempt a broad inventory of what is happening to them within?

Does it frighten Americans to even contemplate that American society may well be slowly but inexorably disintegrating due to some diffuse and complex social disease eating away at its foundation?

Is there for Americans any realistic alternative to behaving like the dead sap who believed to his last anguished breath that if he refused to acknowledge the cancer eating out of his gut and into his spine, he wouldn’t have a problem?

When serial snipers John Williams and John Malvo were arrested, ending their killing spree, the national capital area breathed a sigh of relief.

Why?

Did people pouring out of their houses into the weekend sunshine for the first time in three weeks believe that these particular killers were mutant life forms?

Wouldn’t an obvious logic compel the conclusion that these killers are the products of the peculiarly American social forces that impelled them?

Wouldn’t the same straightforward logic tell us that the Jeffrey Dahmers and Timothy McVeighs of America do not mark the end of a short line, but, rather stand somewhere very near the beginning of what looks from here to be a very long line?

Though the Indian had the metaphysics of it right all along about the timeless place of the human animal in the seamless space of nature, the Indian will neither be seen nor listened to now. The powerful, the heirs of Columbus, the makers, the measurers, the sybarites, the things people, the owners, the one-realm thinkers, the matter laureates, the price-knowers, the patriots—no, they will not listen because they cannot. They hear the world only on the frequency of their tribe, and no outsider has that frequency. They will not hear the Indian or the black or the brown or the poor or the prescient or the wise. They will only hear the sound of guns, their own guns, aimed at them from without, aimed at them by them from within. But even then they will listen to no voice but their own same voice. They were built a long time ago to do only this. To kill themselves, to kill us all, not crudely, but very efficiently, with science.

It is not possible that the United States invaded Iraq for humanitarian reasons.

But why, then?

We’ve only to connect the dots from Columbus to the present to discover the likely answer. The line between the dots will depict once again the simple, open, age-old face of Western material greed.

America’s most important enemy, at least the first in line in the causal chain of such, is America itself, this being the result of a ever-present cocksureness that our runted ruinous social values are like everything else about America the very, very best in the history of civilization.

America has never been more dangerous to the world than now. Wounded lion, judgment warped by anger, no longer killing for food alone, bilnd with the cool, organized rage of the European of the species, serving notice now to the entire planet, shedding all pretense, dispensing with all of its tribe’s thin shibboleths about justice and fairness and other such bullshit that great powers talk when great powers aren’t angry.

White folks have always been rather flamboyantly invisible to themselves, but never before like now.

Decades before a black army unit, the 369th infantry (or Harlem Hellfighters), bested the Germans in WW I while becoming he first U.S. unit to reach the Rhine River, Frederick Law Olmsted dreamed of civilizing a teeming, fractious New York by building in the center of Manhattan a huge park in which the city’s warring social classes could mingle and find, quite literally, common ground. African-Americans, however, were excluded en masse from the construction crew of this massive metaphor so as not to offend the Irish. While stories like this would surprise no nineteenth-, twentieth-, or twenty-first-century African-American, white folk would likely respond, in so many words, with a slightly bemused, “But what’s your point?” The point is they never seem to say what they’re doing to people until the hue and cry is loud enough to melt an iceberg. Even then, the wrongdoing, no matter how egregious, never destroys a reputation but falls merely into the “oh that” bin of backstore history forever.

You see, the fact is, to the industrialized white societies of the world, we don’t count. The Iraqis don’t count. The Palestinians don’t count. Nelson Mandela doesn’t count. Nobody counts unless you do what you are told to do ...and then you still don’t count. Just try to change the course of their conquest events, the hegemony stuff. You’ll see.

Blacks, somehow, have an understanding of this, as if it were hammered onto the template of their common social experience in America. Three out of five blacks oppose the war in Iraq, while only one out of five whites opposes the war. Blacks, however, are almost nowhere to be found in the ranks of the American antiwar demonstrations. Why the discrepancy? Oh we know. Know down deep. Know how to husband our stores and shelter our worn flints, how to use our weathered energy. Know that whites don’t give a shit what we think. Never did. Never will.

From Columbus forward, I know of no sustained contact with Western whites that black and brown peoples and their cultures have survived undevastated, anywhere. From the northernmost point in North America to the bottom of South America, western whites have over time undermined every indigenous culture that they have encountered , with disturbing contemporary social consequences.

It has never failed to hold true. Western whites, once well inside the place of another’s different, less pugnacious, more welcoming culture, destroy it, root and branch. For inexplicable reasons, they are seemingly constrained by some aberrant force of nature to disparage all culture, all history, all religion, all memory, all faces, all life not theirs. They simply cannot come—their soldiers, their preachers, their teachers, their investors, their nobodies—without taking.

Since the age of Christopher Columbus, exemplar extraordinaire, wealthy white Western societies have employed the exploit , dump and bury method as the principal modus operandi for engaging a red, brown, and black world they, over a period of more than five centuries, enslaved, slaughtered, suppressed, and stole from. The resultant socioeconomic damage is deep and far-reaching. It would seem clear, at least in the black world, that any repairs of significance would have to begin with a full confession from the modern beneficiaries. Europe. America. And Western whites generally, all of whom are born to relative advantage because all of this happened.

For all of my life, I had wished only to live in an America that would reciprocate my loyalty, a country that would exhort from the several and diverse mounts of its decision-making authority an ideal of public candor and unconditional compassion, a country that would say without reserve to its disadvantaged, to its involuntary victims, to Native Americans, to African Americans, to the wretchedly poor of all colors, stripes, tongues and religions, that your country wronged you, wronged you in separate and discrete ways, wronged you with horrific and lingering consequence, wronged you, in some cases, from long ago and for a very long time, wronged you to a degree that would morally compel any civilized nation’s serious and sustained attention.

Were America Norway or Sweden or the Netherlands, I’ve little doubt that it would behave with a larger and more embracing spirit. Were America more racially homogenous, where America white, were it not riven with the sapping fears and bigotries of color, were it not gripped by a sheer meanness given rise to by the seismic aftershocks of racial divisiveness, were it not money’s ready catapult, were it not a fiction of its creed, its voters opiate and the demagogue’s toy, were it able to comprehend how race alone affects, distorts, obscures virtually everything that America does at home and abroad, were it inclined to brave but a short season of honest self-examination, I might have remained in the only country I have ever really known and once tried to love.

[B]ecause America is less socially compassionate than Western Europe, in degrees directly proportional to the incidence of blackness among its white, whiter and whitest allies, racism of the virulent and distorting stripe penalizes poor white Americans right along with poor black Americans. Few thoughtful people would doubt that were America as white as Sweden, universal health care would have been the law of the land decades ago.

Relatively few white people will read this book. Judging from letters I have received in response to previous books, I am extrapolating a guess that whites who read black-authored non-fiction books largely read those that applaud or absolve white society of the social dilemmas of blacks. In order to win the white reader’s attention, our social difficulties must be written of as unascribable and past-less, even to be of our own essential making. Failing meeting such conditions, black writers suffer from white readers a banishment of subjective nonexistence. They simply do not want to hear about the causes and consequences, even when the consequences have serious implications for the well-being of the general society.

Americans tend to see the outside world in much the same way. For those in America who know me, or know of me, in leaving the United States, I will have disappeared into thin air. I will continue to exist to them, but the new existence will be technical and unvisualizable. I will have left from, but I will not have arrived to. At least not to any one place they ever heard of or cared much about.

Perhaps there is a new science here to be found. The DNA of nationality. Or more narrowly, American DNA. Getting right to the heart of it, white American DNA. Arrogance socialized too long. Absorbed into the genes. Then there would be no hope. The victim can’t understand. I mean the victim really cannot. It can’t do the transpositions. It has a dyslexia of empathy. Many will die on both sides because the other people can’t understand that the victims just can’t understand. Genetically, I mean.

Considering America’s new hyperpower status in the world, this national genetic illness of America’s should make the world very nervous.

No comments:

Post a Comment