The Foundering Fathers and the White Roots of Peace

Part One: The Death of Democracy in America

Among these widely differing families of men, the first that attracts attention, the superior in intelligence, in power, and in enjoyment, is the white, or European, the MAN pre-eminently so called, below him appear the Negro and the Indian. These two unhappy races have nothing in common, neither birth, nor features, nor language, nor habits. Their only resemblance lies in their misfortunes. Both of them occupy an equally inferior position in the country they inhabit; both suffer from tyranny; and if their wrongs are not the same, they originate from the same authors.[. . . ]Savage nations are only controlled by opinion and custom. When the North American Indians had lost the sentiment of attachment to their country; when their families were dispersed, their traditions obscured, and the chain of their recollections broken; when all their habits were changed, and their wants increased beyond measure, European tyranny rendered them more disorderly and less civilized than they were before. The moral and physical condition of these tribes continually grew worse, and they became more barbarous as they became more wretched. Nevertheless, the Europeans have not been able to change the character of the Indians; and though they have had power to destroy, they have never been able to subdue and civilize them.

Echoing the paranoid rhetoric of Bush's `frivolous lawsuit'-panic, conservative columnist Malcolm Wallop's September 2002 discussion of "litigation" as the "death of democracy" seems unwittingly prescient in light of a pending legal backlash with the potential to expose this most recent assassination attempt against democracy. Wallop writes:

America's constitutional representative democracy is under attack. This plot is not being carried out by terrorists or an opposing army, but by greedy and power hungry lawyers who seek to overthrow our constitutional representative democracy and install in its place a system governance by litigation in which lawyers rule supreme. With the assistance and backing of trial lawyers, small and extreme groups are finding it increasingly easy to bypass and subvert the democratic process and impose their agenda on the rest of society by abusing litigation and manipulating the courts.

Two years prior, in the end stretch of the 2000 presidential race, Christopher Bollyn of the Spotlight Weekly, in an article titled The Death of Democracy - Or - May the Best Hacker Win spoke "before the fact" in terms that may well describe the ex post facto act that weighs heavily on many Americans' minds in conjunction with the "death of democracy" today:

Cook County, IL - Across the United States, in precincts from coast to coast, ballot-counting computers equipped with cellular telephony and two-way modems have counted the votes of the American people. These ballot-counting machines, designed and operated by private companies, and the laws that ushered in their use have essentially disenfranchised citizen election judges from the vote-counting process and relegated them to insignificant roles as public servants working for private business on election night.Computer programmers leave no fingerprints inside a computer, what happens inside it cannot be seen, and its records, and printouts can be fixed to conceal whatever an operator wants to keep secret. However, here and in other key jurisdictions around the nation, election judges have signed off on tally tapes of computer-generated vote counts without any actual verification on their part that the tally is correct.

Democracy's four-year long funeral has stretched already sagging nerves on the far left: Manuel Valenzuela's December 16, 2004 three-part series on the "Death of Democracy" is indicative, and a good read, depending on how much truth you can take in one sitting.

I cite here from Parts II and III, Rise of the Amerikan Nazis: Democracy at Death's Doorstep:

In November 2000 democracy, or the mirage that passed for it, was dismembered, never again allowed to grace America with its cherished principles espousing the power of `We the People.' It was four years ago that democracy inhaled its last breath of life through the asphyxiation of the People's will by the powerful grip of electoral fraud. Today, after four years of having experienced the subsequent results of what fraud helped birth, and now with yet another clear case of electoral fraud under our belts, democracy has been replaced by a mutated and debauched species of democracy, one consisting of televised manipulation of votes through media conditioning, two-party charades controlled and commanded by corporate interests, representative façades that no longer serve the People, and election day fictions of electorate mandates along with fantasies of voter empowerment.All this, combined with the methodical and clandestine rigging of elections by the GOP elite, has resulted in the utter destruction of one of the most honored principles in American history. The beacon of democracy has thus become a bastardized bonfire of duplicity, a sham designed to maintain and control power even as the citizenry is made to believe their voice resonates and steers the country forward. Nothing could be further than the truth.

"We the People," that brilliantly concocted phrase designed for the consumption of the masses, carefully masqueraded yet hardly ever applied, whose fiction has since its creation been unmasked more and more with each passing decade, has now been firmly revealed for the farce that it is through the second coup d'etat in four years to smear the land of greed and the home of the slave. For those residing inside the entrails of the United Corporations of America, now under the firm grip of the Amerikan Nazis, the term created by the Founding Fathers has ceased to exist. It is now nothing more than a phrase rotting away in the dustbins of history, forever to gather dust, slowly decomposing its once protected greatness, discarded by the indifference and abandonment of the same people it was meant to inspire.

Democracy's grave today lies in Florida, with its undertaker, Jeb "Jim Crow" Bush, and its mortician, the good old boys' Grand Old Party, responsible for America's descent into despotism. It was the Sunshine State that first carried the election fraud cancer four years ago, riddled with tumors and chicanery, in time helping spread it to other states and other elections by the greed addicts and power mongers comprising the Amerikan Nazis. Like pollen carried by the wind the virus traveled freely, passing from host to host, from Diebold machine to Diebold machine, infecting Amerikan Nazi minions, from Katherine Harris in Florida to Kenneth Blackwell in Ohio, traitors to a now terminally infected nation, catalysts to mass murder and incalculable crimes against humanity.

While delineating the death of democracy in Hitlerian, proto-fascist terms may seem to represent an ultra-alarmist strain of left-wing extremism, even self-proclaimed "moderate Republicans" like Emmanuel Ortiz have since begun asking themselves whether we Can Stop a Fascist Revolution in America:

No one questions that the 2004 General Election solidified a trend of Republican gains in Federal and state offices nationwide. As a result, many citizen activists--including Greens, Libertarians, Democrats, and increasingly, moderate Republicans (such as myself)--are concerned that the country has reached a crucial inflection point.The 2004 General Election will allow ultra-conservative Republicans to place an almost unassailable stranglehold on Federal and state power in all three branches of government, for decades to come. Well-documented allegations of election fraud in the 2000 General Election and the 2002 Mid Term Election suggest that if wide spread fraud is found to exist in the 2004 General Election, it is part of a larger and, perhaps, darker process that parallels increasing Republican political influence and power.

If Republican gains in 2000, 2002, and 2004 are indeed illegitimate, won through organized fraud, the implications are blood curdling. Faced with this possible scenario, a reasonable person could conclude that the United States is in the final throes of a silent coup d'etat perpetrated over the past four years by a small minority of corporate-backed ultra-conservative interests. In effect, the United States is undergoing an invisible fascist revolution, and no one seems to notice or care.

Googling around with "the day democracy died" can get you into a troubling tangle with time where all roads lead to 9/11. Through the circuitous route of historical amnesia, we arrive at September 11, 1973: the day democracy died in Chile with the CIA-backed ousting of the democratically elected Salvador Allende and the installation of the military dictator Augusto Pinochet. As Mumia Abu Jamal pointed out shortly after the destruction of the World Trade Center towers on 9/11, 2001, many Chileans, including novelist Ariel Dorfman, saw in the events of America's 9/11 a "morbid deja vu." In Dorfman's own words:

During the last 28 years, Tuesday, Sept. 11, has been a date of mourning, for me and millions of others, ever since that day in 1973 when Chile lost its democracy in a military coup, that day when death irrevocably entered our lives and changed us forever....

The BBC provides a more detailed analysis of the events on its site:

11 September, 1973 - The Day Democracy Died in Chile

Salvador Allende holds a unique place in history as he was the world's first democratically-elected Marxist leader of any nation. Sadly, President Allende of Chile's election sent a shiver down the spine of the West who were in the middle of a Cold War, whose egos were reeling from the failure to topple communism in Vietnam and who still felt the threat posed by the Cuban Missile Crisis. Allende was elected to power with 36.2% of the vote in 1970 - his term was to be cut short less than three years later by General Augusto Pinochet. . . .From mid-August 1973 there had been rumblings of a coup brewing in Chile ... At 4am on 11 September, a date that is now synonymous with strikes against democracy, military units stationed throughout Chile reported for action to the leaders of the coup, led by Augusto Pinochet. By 7am, these troops were being deployed ... The most effective operation was carried out in Concepción, the country's third largest city - the military had cut all the phone lines of governmental personnel and had rounded everyone up and placed them on an island to keep them from communicating what had happened to the rest of the world. Once these key players had been removed, the city slipped into military hands. The whole operation took less than 85 minutes to execute.

The BBC's link to a site outlining in greater detail the CIA's involvement in staging the Pinochet-coup is a welcome remedy to most Americans' loss of short-term historical memory, where we are reminded that:

Revelations that President Richard Nixon had ordered the CIA . . . to "prevent Allende from coming to power or to unseat him," prompted a major scandal in the mid-1970s, and a major investigation by the U.S. Senate. Since the coup, however, few U.S. documents relating to Chile have been actually declassified- -until recently. Through Freedom of Information Act requests, and other avenues of declassification, the National Security Archive has been able to compile a collection of declassified records that shed light on events in Chile between 1970 and 1976.--"Chile and the United States: Declassified Documents Relating to the Military Coup, September 11, 1973," by Peter Kornbluh

It's encouraging that at least one New Yorker needed no reminders about the day's history. In September of 2002, just after the one-year anniversary of the Twin Towers' collapse, Frida Berrigan published "9/11 Now and Then" at the Common Dreams Newscenter in which she points to the tragic coincidence of dates by reminding us of yet a third September 11th--the day the first Bush administration made the case before congress that the US should invade Iraq:

Living in New York City one gets the impression ... that Americans are the only ones who have ever suffered. 9-11 gave us a monopoly on grief and provides a justification- a blank check- for U.S. military aggression. At the same time, 9-11 also wipes our slate clean of past crimes and misdeeds. And it is our task to debunk and challenge that notion.It is a great irony that Americans are so into memorials and commemorations but are so ignorant of history. We remember 9-11, but only the 9-11 of last year. [. . .]

In Chile, for example, 9-11 was an important date before 2001. It was the day democracy died, and the U.S. helped kill it. On September 11, 1973 the democratically elected government of President Salvador Allende, a socialist who had nationalized private industry (including U.S. owned copper mines), was overthrown in a military coup underwritten by the USA. Richard Nixon gave the CIA $10 million to help make it happen. With U.S. support, General Pinochet took power and ushered in an era of repression, disappearances, killings, fear and silence. The wounds of that coup-the killing and disappearances of more than 3,000 people-have not healed, in large part because there has been no justice.

As our government prepares for war on Iraq, we can remember another 9-11. On September 11, 1990 the first Bush administration made the case before Congress that the United States should invade Iraq.

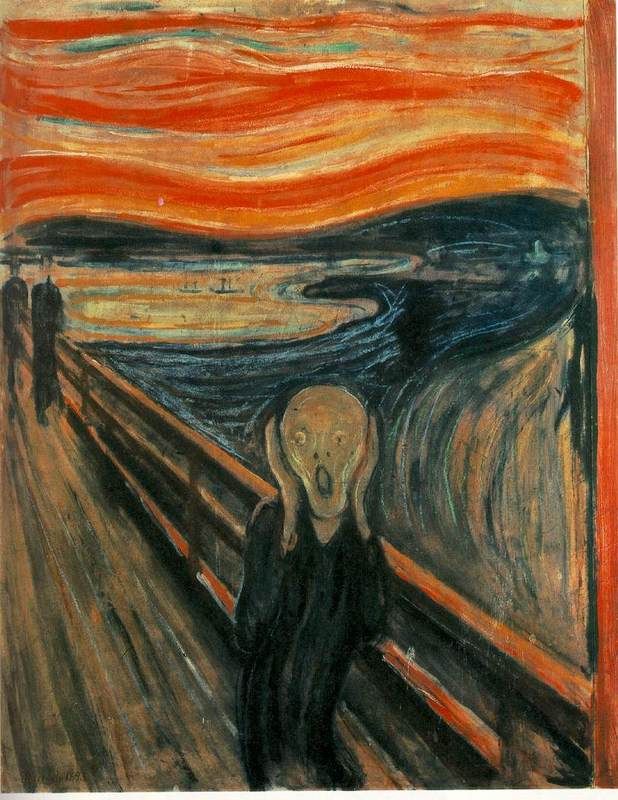

Chief Joseph, Sitting Bull, Geronimo, Red Cloud

George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Theodore Roosevelt, Abraham Lincoln

Image: David Behrens

If a shred hope is to be excavated from declarations of democracy's death; if there's any shot at resurrecting a dead democracy, we must return to the place of its birth. For most Americans, that means a pilgrimage to the Founding Fathers, from there to the ancient roots of Western culture in Greece and Rome, through Medieval Europe's Magna Carta, the European Enlightenment and finally to the shores of the "New World" where democracy miraculously sprang from the heads and hands of men like Ben Franklin, Thomas Jefferson, James Madison. John Locke and others in an act of Athenian creationism heard round the world. Mainstream America's record of events reads something like this:

literally, rule by the people (from the Greek dAmos, "people," and kratos, "rule"). . . . (1) a form of government in which the right to make political decisions is exercised directly by the whole body of citizens, acting under procedures of majority rule, usually known as direct democracy; (2) a form of government in which the citizens exercise the same right not in person but through representatives chosen by and responsible to them, known as representative democracy; and (3) a form of government, usually a representative democracy, in which the powers of the majority are exercised within a framework of constitutional restraints designed to guarantee all citizens the enjoyment of certain individual or collective rights, such as freedom of speech and religion, known as liberal, or constitutional, democracy.Democracy had its beginnings in certain of the city-states of ancient Greece in which . . .citizens were eligible for a variety of executive and judicial offices, some of which were filled by elections, while others were assigned by lot. . . . Greek democracy was a brief historical episode that had little direct influence on the development of modern democratic practices. Two millennia separated the fall of the Greek city-state and the rise of modern constitutional democracy.

Modern concepts of democratic government were shaped to a large extent by ideas and institutions of medieval Europe....Gatherings of representatives of these interests were the origin of modern parliaments and legislative assemblies. The first document to notice such concepts and practices is Magna Carta (q.v.) of England, granted by King John in 1215.

Also of fundamental importance were the profound intellectual and social developments of the Enlightenment and the American and French revolutions . . .. Two seminal documents of this period are the American Declaration of Independence (1776) and the French Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen (1789).

Representative legislative bodies, freely elected under (eventual) universal suffrage, became in the 19th and 20th centuries the central institutions of democratic governments. In many countries, democracy also came to imply competition for office, freedom of speech and the press, and the rule of law. -- Excerpt from Encyclopedia Britannica Entry "Democracy"

When I sat down to put this piece together a few giga-googles ago, my intent was to write about the birth of democracy in America: that is, to return to the origins of the United States Constitution and legislative system in the "Great Law" of the Iroquois League. I wanted to elaborate on some points made in an article recently published by the American Philosophical Association's division on American Indians in Philosophy, where I wrote:

Five hundred years ago, this continent was peopled by a population who shared the same fundamental conviction that it is wrong to derive nourishment from the food placed on someone else's plate. This conviction went hand-in-hand with the notion that it is a shameful thing for one man to be in possession of great wealth while others go hungry. Both ideas emanated from and served the interests of collective survival-then came "rugged individualism" and collective interests were clear-cut from the landscape in order to make way for the pilgrimages of "self-made" men.The Six Nations are the founders of the Oldest Living Participatory Democracy on Earth, not the Greeks and not the "foundering fathers":Yet it's not as though there was no mutual exchange of ideas between the indigenous populations of the Americas and the incoming settler populations--this much is evidenced by the fact that the US constitution was based on the prevailing system of government created by the Iroquois.

This example is ideally suited for demonstrating the dangers inherent in an incomplete or modified appropriation of indigenous concepts into western systems of thought and behavior: whereas the Iroquois League of Nations was a system of government based not on a principle of "majority rules" , but rather one of consensus, the US Constitution changed that part of the system to create a situation in which the country is in a chronic state of strife because any time the "majority rules," the presence of a disaffected "minority" is guaranteed. In the Iroquois system, all parties sat down at the table to draft solutions that everyone could live with. Another major departure the "founding fathers" introduced to the Iroquois system was to establish a government of, by and for the people. The Iroquois system was a government of and by the people for future generations. This "minor" divergence from the source culture's blueprint has contributed substantially to the social, economic and political short-sightedness for which this country has since become infamous.

(The original conference version of this article is available online at Manger Malade: Eating Disorders and the North American Drum Community)

The people of the Six Nations, also known by the French term, Iroquois Confederacy, call themselves the Hau de no sau nee (ho dee noe sho nee) meaning People Building a Long House. Located in the northeastern region of North America, originally the Six Nations was five and included the Mohawks, Oneidas, Onondagas, Cayugas, and Senecas. The sixth nation, the Tuscaroras, migrated into Iroquois country in the early eighteenth century. Together these peoples comprise the oldest living participatory democracy on earth. Their story, and governance truly based on the consent of the governed, contains a great deal of life-promoting intelligence for those of us not familiar with this area of American history. The original United States representative democracy, fashioned by such central authors as Benjamin Franklin and Thomas Jefferson, drew much inspiration from this confederacy of nations. In our present day, we can benefit immensely, in our quest to establish anew a government truly dedicated to all life's liberty and happiness much as has been practiced by the Six Nations for over 800 hundred years.There is ample evidence to indicate that many of the basic democratic principles and practices which have since gone by the name of "American democracy" and are often falsely attributed to non-indigenous models were in fact directly inspired by the Iroquois Confederacy.The Six Nations and the Oldest Living Participatory Democracy on Earth

Benjamin Franklin, in particular, is known to have greatly "appreciated" and selectively "appropriated" the blueprints for democracy outlined and practiced by the Six Nations of the Iroquois League. In his 1988 publication, Indian Givers: How the Indians of the Americas Transformed the World, Jack Weatherford identified Franklin as the first of the founding fathers to have taken the Iroquois system seriously as a model for a functioning democracy. Weatherford writes:

Benjamin Franklin first became acquainted with the operation of Indian political organization in his capacity as official printer for the colony of Pennsylvania. His job included publication of the records and speeches of the various Indian assemblies and treaty negotiations, but following his instinctive curiosity, he broadened this into a study of Indian culture and institutions. [. . .] The colonial government of Pennsylvania offered him his first diplomatic assignment as their Indian commissioner. He held this post during the 1750s and became intimately familiar with the intricacies of the Indian political culture and in particular with the League of the Iroquois. After this taste of Indian diplomacy, Franklin became a lifelong champion of the Indian political structure and advocated its use by the Americans...Speaking to the Albany Congress in 1754, Franklin called on the delegates of the various English colonies to unite and emulate the Iroquois League...--Jack Weatherford, Indian Givers, 136In his seminal work on the subject, Forgotten Founders , Bruce E. Johansen sets out "to weave a few new threads into the tapestry of American revolutionary history, to begin the telling of a larger story that has lain largely forgotten, scattered around dusty archives, for more than two centuries" and argues "that American Indians (principally the Iroquois) played a major role in shaping the ideas of Franklin (and thus, the American Revolution)." Johansen "seeks to demolish what remains of stereotypical assumptions that American Indians were somehow too simpleminded to engage in effective social and political organization," and concludes that, "no one may doubt any longer that there has been more to history, much more, than the simple opposition of `savagery' and `civilization.'" Johansen tells us that

History's popular writers have served us with many kinds of savages, noble and vicious, "good Indians" and "bad Indians," nearly always as beings too preoccupied with the essentials of the hunt to engage in philosophy and statecraft.

This was simply not the case. Franklin and his fellow founders knew differently. They learned from American Indians, by assimilating into their vision of the future, aspects of American Indian wisdom and beauty. Our task is to relearn history as they experienced it, in all its richness and complexity, and thereby to arrive at a more complete understanding of what we were, what we are, and what we may become.Forgotten Founders, Benjamin Franklin, the Iroquois and the Rationale for the American Revolution

In a subsequent (1990) work, co-written with Donald A. Grinde, Jr., Johansen writes in the introduction:

... American history will not be complete until its indigenous aspects have been recognized and incorporated into the teaching of history. [...T]he objective of the contemporary debate should be to define the role Native American precedents deserve in the broader ambit of American history. . . . the character of American democracy evolved importantly . . . from the examples provided by American Indian confederacies which ringed the land borders of the British colonies. These examples provided a reality, as well as exercise for the imagination . . .. In this book, we attempt to provide a picture of how these native confederacies operated, and how important architects of American institutions, ideals and other character traits perceived them. ...Native America had a substantial role in shaping all these ideas, as well as the events that turned colonies into a nation of states. In a way that may be difficult to understand from the vantage point of the late twentieth century, Native Americans were present at the conception of the United States. We owe part of our national soul to those who came before us on this soil.

The full text and a user-friendly, hyperlinked summary of this book is available at Exemplar of Liberty: Native America and the Evolution of Democracy

Documentation from a 1988 conference at Cornell University was compiled and published, edited by Jose Barreiro, in Indian Roots of American Democracy . Google didn't cough up much more than a 1993 discussion of this title by Howard L. Rheingold in the Whole Earth Review.

But it is Weatherford who touches upon my reasons for speaking in terms of "foundering "Even though the Founding Fathers finally adopted some of the essential features of the Iroquois League, they never followed it in quite the detail advocated by Franklin." The disastrous fallout of this sort of "selective appropriation" is evident in the death throes of democracy we witness today, and it is my hope that in more closely examining the "White Roots of Peace" that represent the "Indian Roots of American Democracy," we may be able to determine why democracy in America has failed so miserably.

My intent is to focus in this final section on three particular points in which the Foundering Fathers faltered by failing to follow the features of the Iroquois League in detail, choosing instead to introduce changes which, each in its turn, led to breaches of the underlying social contract which has ultimately caused the entire system to collapse. But before seeking to disentangle this "thread", let's look at what is meant by the "white roots of peace," for this is the structural and conceptual model-that is, the basic constitutive premise-upon which the democratic principles of the Great Law of the Iroquois rest. These are the real roots of democracy in America, and in this sense, it is here that we must return in order to get at the truth about the birth of democracy in America.

The final chapter of Jack Weatherford's Native Roots: How the Indians Enriched America is called "The White Roots of Peace." Weatherford writes:

The Hiawatha Wampum survives as the oldest constitution in North America, perhaps the oldest in the world. . . . it signifies the union of the nations of the Haudenosaunee, the Iroquois League, founded approximately six hundred years ago by Deganawidah and Hiawatha.

. . . The symbols depict four squares joined like the links of a chain, with a tree in the center of the belt. They represent the nations of the league united with one another by the chain of friendship. The tree signifies law and peace, and its branches represent the security and shelter given to humans by the law. Deganawidah named this constitution Kaianerekowa, and he taught that peace and law had to be inseparable (Native Roots, 286).

Deganawidah, the leader of the Haudenosaunee, persuaded all the warriors to bury their weapons in a cavern beneath a certain tree-once he'd established peace, he planted a new one in honor of that peace and so that future generations would be reminded of his "philosophy of Good Mind" as a pre-condition for peace. This became the Great Tree of Peace and represented the structure and Spirit of the Iroquois Great Law of Peace. Weatherford elaborates on the White Roots of Peace:

The tree had four large white roots, each of which grew in a different direction. Deganawidah prophesied that the roots of the tree would eventually grow to the far parts of the world, that in time the four roots would grow to include new nations of people not yet known. From many nations they would create one.

This story was already an ancient one when the first settlers came from Europe, and the native people shared their knowledge of the Good Mind with the newcomers. The new people came to live under the Great Tree of Peace, but they did not know its history. They did not know of the weapons buried in the earth, or of the white roots of peace that needed to be watered and nourished to help the tree grow. (287)

The Great Tree of Peace is not merely symbolic in nature: it is also the botanical blueprint for a constitutional, binding "Great Law" in a functioning participatory democracy that existed for hundreds of years before the settler population arrived. It represents the conceptual model for a tried-and-true democratic system of government , The Iroquois Constitution.

Since the first person to heed Deganawidah's appeal to peace was a woman, Jikohnsaseh, he honored her in the Great Law of Peace in this way:

he selected women as the Clan Mothers, to lead the family clans and select the male chiefs.Women were given the right to the chief's titles and the power to remove dissident chiefs. Jikohnsaseh, by hearing of her actions, taught me to respect women and honor their role. Women are the connection to the earth and have the responsibility for the future of the nation. Men will want to fight. Women know the true price of war and must encourage the chiefs to seek a peaceful resolution.

The Iroquois were and remain a matriarchal, matrifocal and matrilineal society. Women were actively involved in issues of governance, and, in fact, assigned crucial, decision-making roles: according the Great Law, women not only appoint, but also have the power to impeach the representatives they have selected and to determine when and if said representatives have failed to uphold or in any way infringed upon the principles of the Great Law.Women's active participation in government did not sit well with the Founding Fathers who certainly did not leave their patriarchal structures and prejudices behind when the left the motherland and set out in search of a New World. Grinde and Johansen provide a fairly in-depth analysis of this in Exemplar of Liberty

One aspect of native American life that alternately intrigued, perplexed and sometimes alarmed European and European-American observers, nearly all of whom were male during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, was the role of Indian women. In many cases they held pivotal positions in native political systems. The Iroquois women, for example, nominated men to positions of leadership, and could "dehorn," or impeach, them for misconduct. Women usually approved men's plans for war. In a matrilineal society, and nearly all the confederacies that bordered the colonies were matrilineal, women owned all household goods except the men's clothes, weapons, and hunting implements. They also were the primary conduits of culture from generation to generation.

Already in 1987, David Yarrow wrote of the New World Roots of American Democracy

It is unfortunate that the Iroquois' central role in the creation of the United States government has apparently been a well kept secret. For The Great Law provides uniquely valuable instruction in the arts of politics and law, negotiation and diplomacy, disarmament and government.The search for world peace is of utmost concern to all men and women of good will today. . . .We must assure this deeper heritage of freedom is rediscovered and exposed to national attention once more. Beneath the great gushing growth of modern American culture, hidden and forgotten, lie the true roots of freedom, democracy and peaceful co-existence.

Let us hope modern civilization will pause its arrogant, headlong rush to catastrophe long enough to look and take note. For if we follow the White Roots of Peace back to their source, we find men and women of the Iroquois Nations gathered around a hole into which Peacemaker cast the weapons of war. There we find the spiritual inheritance of all humanity: One Peaceful World, the United Nations of the human family.

Selective Appropriation: Where the Fathers Foundered

The democracy we now witness gasping its last breath on our doorstep is not the democracy born in ancient Greece and smuggled into the New World on the Mayflower wrapped in the Magna Carta.

Democracy, as we know it, is the partial live birth of democracy for the colonialist population of the Americas, selectively appropriated from the indigenous Iroquois peoples. The founding fathers cannot be said to have given "birth" to democracy in America-at best, they can be said to have been midwives to the birth of democracy among the nation's newcomers. Democracy as we know it today in America is a motherless child whose adoptive fathers threw the baby out with the bathwater at birth--by way of selective appropriation.

When I speak in terms of "selective appropriation," it is in anticipation of the inevitable question: well, isn't it an honor to the Iroquois, isn't imitation the sincerest form of flattery? My answer to that is that the "borrowing" is not what's objectionable, it's the selective borrowing--by taking only parts of the system established by the Iroquois and altering significant, indeed paradigmatic or constructive elements--the foundering fathers violated the spirit of the system. This is what I call "selective appropriation."

I have already mentioned three central points of departure from the Iroquois League model which, in my opinion, have contributed substantially to American democracy's demise:

1) switching from a principle of consensus to one of "majority rules"

2) forming a government of the people, by the people and for the people rather than of the people, by the people and for future generations

3) allowing for the conceptually inconceivable task of "giving birth" to a democracy to be delegated by men rather than women

The Chiefs do not vote on matters, but discuss them from all perspectives. Each option must be considered. Consensus requires thoughtful analysis and sensitive negotiation. Different points of view must reach a compromise that is acceptable to all. While this requires more deliberation, it eliminates a dissenting minority because no decision is made unless all sides agree.

A majority-rules based system inevitably results in some people gloating in victory and others wallowing in the despair of defeat. Majority rule necessarily creates a discontented minority, so majority rules will never lead to a genuinely peaceful system of governance. As long as there is a clear majority, let's say around 70 to 30, the inherently faulty majority rules system will always falter, but is not likely to collapse. It approaches the breaking point somewhere around 50/50. Even the illusion of a fifty-fifty split in the populace of a majority-rules system can precipitate the collapse by balancing the scales in the majority-minority dichotomy so that six of one basically becomes half a dozen of the other while +/- fifty percent of the population gets to keep all the marbles and the remaining +/- fifty percent loses its marbles. The result is sheer insanity.

Presently, political, social and economic decisions in this country are with an eye for their impact on the next fiscal quarter-at best, they are calibrated with regard for their four-year (i.e., one presidential term) consequences. This has led to the short-sightedness, historical amnesia and short-term memory loss for which this country has since become infamous. The basic assumption underlying the notion of a government "for the people" as it is understood by beneficiaries and subjects to the US Constitution is that people living in any given "now" make decisions on their own behalf and primarily to protect their own interests-in the here and now; while the Preamble, in stating the intent to "secure the blessings of liberty to ourselves and our Posterity" gives a casual nod to the sake and the stake of the future, there is no real commitment to "future generations" in the principle or in the practice of US Constitutional law and governance.

Women as Sources of Authority versus Women as Subjects of Authority

"Savagery to Civilization"

We, the women of the Iroquois

Own the Land, the Lodge, the Children

Ours is the right to adoption, life or death;

Ours is the right to raise up and depose chiefs;

Ours is the right to representation in all councils;

Ours is the right to make and abrogate treaties;

Ours is the supervision over domestic and foreign policies;

Ours is the trusteeship of tribal property;

Our lives are valued again as high as man's.

We will never know what the course of history would have been had the foundering fathers taken their lead from the Iroquois on this point, and speculation in this regard will get us nowhere. Logic, however, might.

The following statement presented to the United Nations in 1995

by Carol Jacobs, Cayuga Bear Clan Mother, outlines some of the logic behind women's position in matriarchal cultures and points to plausible reasons for not only allowing women to participate in a functioning democracy, but mandating that they assume prominent decision-making roles:

Among us, it is women who are responsible for fostering life. In our traditions, it is women who carry the seeds, both of our own future generations and of the plant life. . . .It is my right and duty, as a woman and a mother and a grandmother, to speak to you about these things, to bring our minds together on them. . . .

In making any law, our chiefs must always consider three things: the effect of their decision on peace; the effect on the natural world; and the effect on seven generations in the future. We believe that all lawmakers should be required to think this way, that all constitutions should contain these rules. . . .

All too often, these traditions are viewed as "things of the past"-dismissed as long forgotten, now archaic "Indian lore." But that is not the case. Modern-day Haudenosaunee have included this point in their list of "Ten Important Points to Remember":

We exist as distinct peoples in the 20th century. The Haudenosaunee are unique in that we maintain one of the very few traditional governments in North America, free from the oppression of the Bureau of Indian Affairs and free from the lunacy of tribal elections. Our leaders are selected according to the oldest constitutional democratic systems.

Democracy may be dead for most of America, but democracy's origins are still alive in the lives and practices of the peoples who created them. Democracy may be dead, but its white roots remain. The legend, the spirit and the Great Law of the Land live on in the Iroquois Nations today. They can be visited at their website: Mohawk-Oneida-Onondaga-Cayuga-Seneca-Tuscarora

Jake Swamp, widely considered one of the most knowledgeable sources on The Great Law, passed in 1998, but his spirit lives on in the Tree of Peace Society he founded in 1984; here, a brief biography from their site:

Tekaronianeken, Jake Swamp with thirty years as a Mohawk chief and representative on the Grand Council of the Iroquois Confederacy has offered a wide range of experience in indigenous, environmental and social issues both locally and internationally. Beginning in the summer of 2000 Jake has been an active participant in the National Conference of Community and Justice and met with President Clinton and many other religious leaders to discuss reconciliation and cultural diversity. Jake was also among the Iroquois delegations that addressed the United Nations Millennium Peace summit, August 2000.Jake has inspired a new generation of Mohawk leaders and teachers who are now taking the place of Elders in the communities of the Iroquois and was directly involved in the creation of the Akwesasne Freedom School - a Mohawk language immersion school of critical acclaim that has been an inspiration to many First Nation peoples in the United States and Canada. Jake has inspired hundreds of people of many races and culture through working with a number of influential organizations. As result of his thirty years experience as a sub-chief of the Mohawk Nation and international ambassador, Jake has been traveling around the world, planting "Trees of Peace" in diverse places such as Israel, Australia, South America, United Nations, St. Johns' Cathedral in New York City and over twenty colleges and universities in the United States and Canada. Through his tree planting efforts, Jake has inspired the planting of over 200 million trees. Jake continues to inspire many college students of all races and backgrounds through his extensive lecturing schedule which takes him to over 10 universities and other speaking engagements a year.

A brief biography of Oren Lyons, another well-versed expert on the Great Law, reads as follows:

Oren Lyons is Faithkeeper of the Turtle Clan, Onondaga Nation, Haudenosaunee (Six Nations Iroquois Confederacy). Oren has also been active in international indigenous rights and sovereignty issues for over three decades at the United Nations and other international forums. He is an Associate Professor in the American Studies Program at the State University of New York at Buffalo. He is also the publisher of "Daybreak," a national Native American news magazine.

Here is an excerpt from Oren Lyons' statements addressing delegates to the United Nations in the opening ceremonies for the "The Year of the Indigenous Peoples" (1993):

Our societies are based upon great democratic principles of the authority of the people and equal responsibilities for the men and the women. This was a great way of life across this Great Turtle Island and freedom with respect was everywhere. Our leaders were instructed to be men of vision and to make every decision on behalf of the seventh generation to come; to have compassion and love for those generations yet unborn. We were instructed to give thanks for All That Sustains Us.The full text of his address, together with many related links, is available here.

It is from these living traditions, from these living men and women that we might turn for insights into resurrecting and learning to sustain our democracy.

No comments:

Post a Comment